By Erin Carroll

An eclectic group of graduate students from departments and schools across the country came together for a conference at Washington University. These History, American Studies, Public Health, Sociology, Anthropology, Education, English, Public Policy, Geography, Government Gastronomy, Communications, Urban Studies, and Cultural Studies graduate students were brought together by the fact that they all also identify with the relatively new, interdisciplinary academic field known as “food studies.” All have found themselves dedicating their scholarship to exploring questions related to food: how we produce it, consume it, trade it, and relate ourselves and others to it and through it.

The three-day conference, held at Washington University in St. Louis from October 19 through 21, was organized by the Graduate Association of Food Studies (GAFS). Founded by current Wash U Anthropology PhD student Brad Jones in 2014, as the official graduate student caucus of the Association for the Study of Food and Society (ASFS) the GAFS strives to connect graduate students interested in food and promote their exceptional work. This past weekend’s events were the second iteration the Association’s Future of Food Studies Conference, held for the first time at Harvard University in 2015. After two very successful conferences, the Association has decided to make the Future of Food Studies Conference an annual event.

The three-day conference, held at Washington University in St. Louis from October 19 through 21, was organized by the Graduate Association of Food Studies (GAFS). Founded by current Wash U Anthropology PhD student Brad Jones in 2014, as the official graduate student caucus of the Association for the Study of Food and Society (ASFS) the GAFS strives to connect graduate students interested in food and promote their exceptional work. This past weekend’s events were the second iteration the Association’s Future of Food Studies Conference, held for the first time at Harvard University in 2015. After two very successful conferences, the Association has decided to make the Future of Food Studies Conference an annual event.

In line with the mission of GAFS to foster the graduate food studies community, the Conference is organized and attended exclusively by graduate students. The panels are unique opportunities for students to present their work to a truly supportive and engaged room of their peers. Given that the presenters are students at all points in their graduate experience, many who have only just begun, the presentations tend to cover initial field work, findings and conclusions. With time left to expand and refine their work, this means that students are able not only to question and critique each other in hindsight, but to critique constructively, sharing resources and ideas of how each presenter might improve their project in the future.

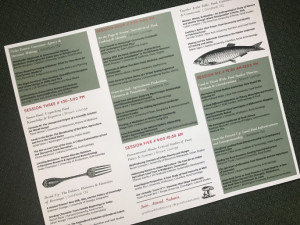

Session presentations were given by 45 students, from 22 different disciplines at 27 schools in nine countries. Topics reflected this interdisciplinarity well, ranging from gendered labeling in the craft beer industry to dystopian interpretations of human-microbe relations. Several of the sessions focused on questions of identity. At sessions titled “Food, Identities & Knowledges: Ongoing Debates & Emerging Questions,” “Drink Up: The Politics, Histories & Identities of Beverages,” and “On the Page & Screen: Narratives of Food, Cooking & Identity,” researchers explored the ways that humans construct and understand their personal and cultural identities through the types of foods they consume, produce, sell and share, and the ways they ritualize their consumption. Emily Contois of Brown University, for example, gave a fascinating presentation on “The Manliest Low-Calorie Soda in the History off Mankind” during which she discussed how consumption of diet sodas constructs understandings of masculinity.

Where the sessions on identity were often light and exploratory, other sessions asked more critical questions of how food systems and narratives can create, perpetuate and illuminate inequities. At one session themed “Digging in: Critical Approaches to Studying Food, Race & History,” two students from the University of Missouri in the Rural Sociology and Agricultural Education departments collaborated on a project in which they investigated their own institution’s history of treating race, gender and class within its food system. At another, two University of South Florida of students presented independent research on issues of food insecurity from the perspectives of public health and Anthropology. The conference also included more practical sessions which addressed topics of food production, marketing and regulation from a variety of disciplines, as well as a final session on the theories and methods of the formal field of Food Studies itself.

In addition to providing the opportunity for students to present and discuss their work, the conference also served the important purpose of strengthening Food Studies itself; of not only discussing the future of food studies, but actively shaping it. At a Friday night social at Three Kings Pub and a Saturday afternoon field trip to a local urban farm, participants formed and reinforced a graduate student community with which they can collaborate throughout their careers. This community acknowledged that together they would decide the direction and prestige of a young and eclectic field that, two decades ago, was little more than a topic of interest. As Jones noted in his opening address to the group, “As graduate students researching food, the Future of Food Studies will be to a large extent determined by us. Indeed, look around, the future of food studies is us: it’s in the challenges we face, in the intellectual projects we pursue, in the collaborative networks we cultivate together.” Through challenging each other to produce exceptional work, creating networks and sharing resources, the students ensure that the field will continue to grow and be taken seriously by more traditional and entrenched academic disciplines.

In addition to providing the opportunity for students to present and discuss their work, the conference also served the important purpose of strengthening Food Studies itself; of not only discussing the future of food studies, but actively shaping it. At a Friday night social at Three Kings Pub and a Saturday afternoon field trip to a local urban farm, participants formed and reinforced a graduate student community with which they can collaborate throughout their careers. This community acknowledged that together they would decide the direction and prestige of a young and eclectic field that, two decades ago, was little more than a topic of interest. As Jones noted in his opening address to the group, “As graduate students researching food, the Future of Food Studies will be to a large extent determined by us. Indeed, look around, the future of food studies is us: it’s in the challenges we face, in the intellectual projects we pursue, in the collaborative networks we cultivate together.” Through challenging each other to produce exceptional work, creating networks and sharing resources, the students ensure that the field will continue to grow and be taken seriously by more traditional and entrenched academic disciplines.

To this end, the Conference also provided participants with examples of what exceptional work in Food Studies looks like. During a Thursday night plenary address and a Friday evening keynote presentation, Drs. Alison Alkon of the University of the Pacific and Krishnendu Ray of New York University each presented on their research and experiences in the field. Attendees were also provided the opportunity to engage directly with distinguished faculty through a panel of Drs. Glenn Stone and Venus Bivar of Washington University in St. Louis and Dr. Catarina Passidomo of University of Mississippi. Each panelist discussed the paths their careers had taken and the lessons they had learned from their disciplines (Anthropology, History, and Geography, respectively), sharing every bit of advice they could muster with the graduate students and answering their questions.

One topic discussed during the panel and throughout the weekend was the interdisciplinary nature of the field of food studies, and the potential tradeoffs this creates between breadth and depth. While having a wide range of disciplines means that questions are addressed with expertise from robust, complementary perspectives, it also means that experts often find themselves speaking to people with little experience in their fields. How does the archeologist effectively communicate her processes and findings in paleoethnobotany to the Kinesthesiologist who is examining food literacy as a public health tool, and vice versa? How effectively can they challenge each other?

This tension was discussed openly and often at the Conference. While students and faculty acknowledged that it was an uncertainty in the field which would have to be navigated, they agreed that it was a powerful tool which creates potential for uniquely complex approaches to complex issues; that the interdisciplinarity of food studies creates a network of researchers in complementary fields who can challenge each other to expand the scope with which they engage their topics. As the conference drew to a close with a final flurry of networking and excitement across disciplines, schools and countries, it was clear that everyone had concluded that the future of the “interdiscipline” of food studies was something to be celebrated.

Article written by Washington University in St. Louis undergraduate, Erin Carroll

In text images by Brad Jones

Primary image by Sean Garcia